Help NPSO Sponsor Spalding’s Catchfly!

Last Updated on November 9, 2024 by Tom Pratum

| Help NPSO Sponsor Spalding’s Catchfly! |

| The Rare and Endangered Committee has proposed contributing funds to complete sponsorship of the rare Spalding’s catchfly (Silene spaldingii) from the Rare and Endangered Fund to the Center For Plant Conservation (CPC) as part of their 40th Anniversary Campaign. Our partners at the Oregon Department of Agriculture’s Plant Conservation Program have already partially sponsored this species (in the amount of $2,500) and we want to match their efforts. As part of their 40th Anniversary Campaign, CPC will provide $5,000 in matching funds for every $5,000 raised per plant species. Once a species gets to the full sponsorship level of $10,000, CPC provides their conservation partners $500 dollars annually to help offset the costs associated with collecting seed, growing out plants, and/or conducting research. For Spalding’s catchfly, our partners at the Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank & Plant Conservation Program, will be the beneficiary conservation partner of CPC’s annual funding. Your donations to the Rare and Endangered Fund last year helped us fully sponsor frigid shootingstar (Dodecatheon austrofrigidum) through this same campaign. This means CPC is now providing the Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank $500 annually in perpetuity for management, research, and upkeep of the seed bank accessions of this species. Let’s do the same for Spalding’s catchfly! |

| Frigid shooting star (Dodecatheon austrofrigidum). May 20, 1972. © Wilbur L.Bluhm, Courtesy of OregonFlora. |

| Plant of the Month: Spalding’s Catchfly A Little History: Spalding’s catchfly (Silene spaldingii) was described and named by Sereno Watson, an assistant to the iconic Harvard University botanist, Asa Gray, in 1875. Gray and Watson had received specimens somewhat circuitously from the Reverend Henry H. Spalding through the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Spalding had been part of the original 1836 missionary train to the Oregon country led by Marcus Whitman, who had started the Whitman Mission west of Walla Walla, Washington. He and his wife Eliza were not part of the Whitman Mission but rather settled east of Lewiston, Idaho, near what is now Lapwai, to start their own mission to the Nez Perce. They homesteaded and carried on their missionary duties there until shortly after the Tragedy at Waiilatpu in 1847 (formerly known as the Whitman Massacre) after which they relocated to several budding communities in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, including Forest Grove and Brownsville. He eventually returned to Lapwai to continue missionary work before dying there in 1874. During his initial time at Lapwai, Spalding had befriended and accompanied another well-known botanist, Charles A. Geyer, on some of his explorations of the Nez Perce country in 1844. This relationship appeared to have inspired Spalding sufficiently in the wonder of botany that he eventually collected and pressed many dozens of specimens from the Lapwai, Clearwater River, and Nez Perce region. It was through Geyer’s connections to those at Harvard University through the missionary board that Spalding was eventually able to get his specimens in the hands of Gray and Watson sometime around late 1848 to early 1849, including two specimens of the soon to be described Spalding’s catchfly. The Plant: Spalding’s catchfly is a perennial in the Pink Family (Caryophyllaceae) that emerges in spring from a woody root crown that dies back to below ground in the fall. Typically, in its first and second years, plants produce only rosettes (no flowers) . The roots are large and up to 1-meter deep, making it difficult to transplant but also allowing for prolonged periods of dormancy of 1- to 2-years, but as long as 6-years, where no above-ground vegetation appears. Studies suggest this prolonged dormancy may be an important life history function for survival and reproduction in arid environments as dormant plants are more likely to flower than plants that produced vegetation the year prior. Flowering occurs in July and August but occasionally extends into September when conditions are right. |

| Spalding’s catchfly (Silene spaldingii). August 15, 2011. © Robert L. Carr, Courtesy of OregonFlora. |

| Plants have one to many 20- to 60-centimeter stems that are yellowish-green, villous, and glandular-viscid throughout which makes them densely sticky, often trapping dust, detritus, and/or insects. Each stem bears four to seven (and up to 12) erect pairs of 3- to 7-centimeter long by 0.5- to 1.5-centimeter-wide leaves that attach to swollen nodes along the stem. The ovate to lanceolate leaves are acutely tipped, lack petioles, and are largest at mid stem. The inflorescences are terminal (sometimes axillary distally), usually leafy, and somewhat narrow, with three to twenty flowers. The spreading, ascending, and/or erect flowers are on pedicels that are shorter than the calyces. Flower calyces are tubular-campanulate, obscurely 10 veined (but not netted), and 1- to 1.5-cm long at anthesis, with narrowly lanceolate lobes that are 0.3- to 0.6-cm long. The pale greenish to white emarginate flower petals do not exceed or only barely exceed the calyx lobes and have 4 (rarely up to 6) small appendages on the adaxial surface. Stamens and styles are three in number and roughly equal in length to the petals. The short-stiped fruiting capsules are 1-celled, ellipsoid, slightly longer than the calyx, and opening to 6 teeth. Inside are yellowish brown reniform-shaped, winged seeds, wrinkled with alternating ridges and furrows, inflated, and approximately 0.2 cm long. What distinguishes Spalding’s catchfly from co-occurring Silene species (S. scouleri, S. oregana, S. douglasii, S. csereii, and S. scaposa) is the unique combination of long calyx lobes, short petals that barely exceed the calyx lobes, relatively large, inflated seeds, and the viscid pubescence throughout the plant. |

| Spalding’s catchfly (Silene spaldingii). July 14, 2004. © Angela C. Sondenaa, Courtesy of OregonFlora. |

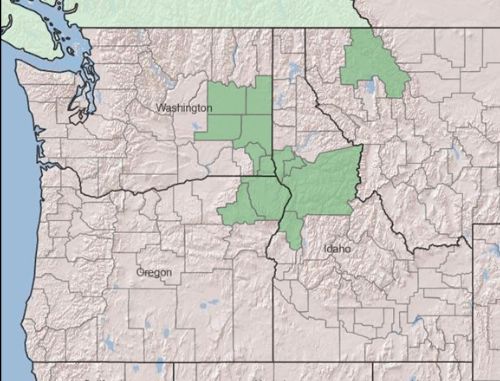

| Spalding’s catchfly is only known from a handful of populations in Wallowa County in northeastern Oregon with several more populations in adjacent southeastern Washington and western Idaho. Additional populations are known from northwestern Montana with the northernmost population just reaching into British Columbia, Canada. |

| Range Map for Spalding’s catchfly (Silene spaldingii). © 2014 Esri | USDA-NRCS-NGCE & NPDT. |

| These populations coincide with five different physiographic regions over its range including: the Blue Mountain Basins of northeastern Oregon; the Canyon Grasslands associated with the Snake River and its tributaries in Oregon, Idaho, and Washington; the Palouse Grasslands of west-central Idaho and southeastern Washington; the Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington; and the Intermontane Valleys of northwestern Montana and southern British Columbia. More specifically, its habitat is often dry to moist bunchgrass or sagebrush-steppe or occasionally open pine habitat in deep loess soils with northerly aspects. Elevations of these habitats are typically between 365-1615 m (1200-5300 ft). Associated dominant species include Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), mountain rough fescue (Festuca campestris), big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), cut-leaf sagebrush (Artemisia tripartita), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), black hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii), and snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus). Spalding’s catchfly is federally listed as threatened throughout its range in the United States. It is listed as endangered in Oregon and threatened in Idaho and Washington. The Montana Natural Heritage Program considers it threatened or endangered throughout its range (but with no state listing). It is listed as endangered in Canada. Primary reasons for listing and conservation concern are due to habitat loss and degradation from human development, livestock grazing, and invasive species; changes in fire frequency, seasonality, and intensity; and, to a lesser extent, susceptibility to herbicide spray drift and off-road vehicle use. The species may suffer from reduced genetic fitness due to population fragmentation. If you enjoyed this article and would like to join NPSO in sponsoring this species, please donate to the Rare and Endangered Fund! –Jason Clinch, Rare and Endangered Committee Chair, Director-at-Large, 2024 References: Center for Plant Conservation. 2024. Profile page for Silene spaldingii (Spalding’s catchfly): https://saveplants.org/40th-anniversary/. Accessed June 21, 2024. Morton, John K. Silene spaldingii. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 25+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 5. http://floranorthamerica.org/Silene_spaldingii. Accessed June 21, 2024. Oliphant, J. Orin. 1934. The Botanical Labors of the Reverend Henry H. Spalding. In: Washington Historical Quarterly. Vol. 25, No. 2. University of Washington Libraries. 2010. Oregon Biodiversity Information Center. 2023. Rare, threatened and endangered vascular plant species of Oregon. Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. January 2023. Oregon Department of Agriculture. 2011. Profile page for Spalding’s campion (Silene spaldingii): https://www.oregon.gov/oda/programs/PlantConservation/ SiteAssets/Pages/AboutThePlants/SileneSpaldingiiProfile.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2024. Oregon Flora Project. 2024. Profile page for Spalding’s campion (Silene spaldingii S. Watson): https://oregonflora.org/taxa/index.php?taxon=8434. Accessed June 21, 2024. Tilley, D., D. Ogle, and L. St. John. 2009. Plant guide for Spalding’s catchfly (Silene spaldingii). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Idaho Plant Materials Center. Aberdeen, ID. 83210. |