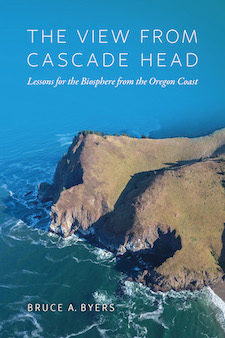

The View from Cascade Head: Lessons for the Biosphere from the Oregon Coast

Last Updated on November 21, 2022 by

by Bruce A. Byers

ISBN 9780870710353

Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon., 2020

The frontispiece reveals that the name Cascade Head in the book title refers to the Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve, which encompasses a number of discrete components, including the Neskowin Crest Natural Research Area, Cascade Head Experimental Forest, The Nature Conservancy Cascade Head Preserve, Sitka Center for Art & Ecology, Salmon River and Estuary, Camp Westwind, and Cascade Head Marine Reserve.

In 15 chapters, Byers tells the story of the Biosphere Reserve, arranging his narrative by he calls the “re” words: resistance, research, restoration, reconciliation, and resilience. Byers uses the metaphor of “the eagle’s view” to unite his essays around these themes and to explore ethical implications for our human behavior and that of our culture. The theme of resistance speaks loudly and clearly as we learn how, in 1973, local individuals (including Senator Bob Packwood), alarmed at encroaching development surrounding Cascade Head, a basalt headland with dramatic ocean views, laid the foundation for what would become the reserve. Their efforts illustrate the first of three lessons presented in the book: the commitment and hard work of individuals can make all the difference.

The Biosphere Reserve encompasses 160 square miles, extending along the central Oregon coast between Neskowin and Lincoln City. In beginning chapters, Byers traces the history of the biosphere concept (it dates to 1890 in Ukraine), a worldwide program “to create a network of places dedicated to monitoring and understanding the diverse ecosystems of the biosphere and developing models and strategies for maintaining or restoring their resilience while still meeting human social, cultural, and economic needs.” Having worked in 34 biosphere reserves in 17 countries, Byers is eminently qualified to reveal the lessons that Cascade Head has to offer.

Over 40 years ago, Byers and I shared an advisor in our graduate programs at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Later, as a biology professor at Linfield College in McMinnville, I led field trips for my students to The Nature Conservancy’s Cascade Head Preserve to study the ecology of temperate rainforests. My plant taxonomy students and I spent weekends at Camp Westwind learning to recognize coastal species. Over the years, I have taken several courses at the Sitka Center for Art & Ecology where Byers was an Ecology Resident in 2018, and we both share a fondness for the molasses bread at the Otis Café. I know this area well, but until I read this book, I didn’t realize how much more there was to learn.

Byers introduces us to a host of ecological concepts, such as succession, species and genetic diversity, nutrient cycling, predator-prey relationships, decomposition, evolution, and symbiosis. We learn the ecological importance of keystone species, such as sea stars that, as dominant predators, maintain species diversity in intertidal ecosystems. Byers documents extensive research that revealed the importance of protecting mature forests for the survival of an entire group of species, including the marbled murrelet, spotted owl, and red tree vole. He outlines how restoration of the Salmon River Estuary was critical to the survival of juvenile salmon and returning adults. Yet, despite extensive research, he highlights a second lesson, that “ecological mysteries” still abound. What explains migratory patterns of grey whales? What caused sea star wasting, and why did the disease suddenly disappear? What is the best way to restore genetically distinct populations of Oregon silverspot butterflies to increase their resilience in coastal prairies?

Byers demonstrates that, over time, researchers have had to increase the scale of their studies from local sites to a landscape level of analysis. For example, research on beavers revealed their critical role in maintaining forest health by regulating the hydrologic cycle on land, reducing runoff and sedimentation of streams. In turn, healthy streams facilitated the return of salmon from the ocean to their natal streams where, upon death, they returned nutrients to the forest. Recognizing this connection between the land and the sea led ultimately to the addition of the Cascade Head Marine Reserve to the larger Biosphere Reserve.

Byers describes a “multi-use shades of green landscape model,” a worldview where ecological, economic and cultural benefits are balanced among stakeholders. He concludes that how we think about our human relationship to nature shapes our individual and collective actions. This third lesson to be gained from the book offers a pathway for reconciliation between often competing interests and opposing worldviews. He shares how his residency at the Sitka Center for Art & Ecology revealed how art and ecology intersect, that art is “one aspect of human ecology, and ecological science is a kind of art.” In this interpretation, art is, like science, an adaptive behavior, helping to protect the biosphere. I recommend this book to anyone interested in gaining a deeper understanding of how the Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve has achieved the goals of UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Program by “becoming laboratories for understanding complex social-ecological systems and models for resolving problems, restoring ecological functions and services, and increasing resilience in the face of climate change and other unpredictable events.”

The book is attractive, easy to read, and graced with lovely illustrations. A timeline table would have helped me follow the incremental addition of the various components that now make up the reserve and, of course, photos of this beautiful site would have been welcome (but would have made the book much more expensive). The only error I found was in reference to Indian hemp (Apocynum cannabinum), which Byers incorrectly described as a noxious weed. Its rhizomatous habit makes it troublesome in gardens and agricultural settings, but this native species is not on the Oregon Department of Agriculture’s list of noxious weeds.

It should come as no surprise that the Cheahmill Chapter will offer five field trips to this incredible area when NPSO is, once again, able to offer an Annual Meeting, perhaps in 2022.

—Kareen Sturgeon, Cheahmill Chapter.